In June, the European Commission will announce its ‘fit-for-55′ package, designed to put the European Union on a pathway to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (below 1990 levels), so as to achieve EU carbon neutrality by 2050. The menu is set to be substantial, with a starter, main course and dessert trolley.

- For starters : the revision of the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) for heavy industry, power generation and intra-EU air traffic, improving its functioning, possibly extending its scope (including to shipping and aviation) and introducing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

- The main course, then: an upward revision of the ambitions of sectors not covered by the quota market, which are responsible for around 60% of emissions: transport, construction, agriculture, waste, and some industries.

- The dessert trolley, finally: revision of the Regulation on land use, land use change and forests (to capture carbon), revision of the Renewable Energy Directive, energy efficiency, energy taxation, revision of the Regulation on CO2 emission standards for light commercial vehicles…

In this menu worthy of the best restaurants currently closed, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) plays a useful, if not indispensable, additional role in strengthening the climate policy instruments. The idea is that producers from particularly emission-intensive sectors face de facto the same carbon pricing whether they are in the UE or not. Exporters into the EU, wherever they come from, would, for example, have to purchase emission allowances upon entering the EU. Companies that can demonstrate a virtuous production process or that are already subject to such a policy in their home country should be offered flexibilities so that these elements are taken into account when calculating the level of the adjustment, in order to encourage greater climate ambition.

The challenge of carbon leakage

According to the meta-analysis by Branger and Quirion (2014) and the literature review by Carbone and Rivers (2017), for every 10 tons of greenhouse gas emissions avoided in a country or region implementing more ambitious climate policies, emissions in the rest of the world would increase by 0.5 to 3 tons. These leakages can be either direct (relocation of carbon-intensive production, loss of market share by countries with ambitious climate policies at home and in the world) or indirect (via a drop in energy prices at the global level due to lower demand from countries with ambitious climate policies). If econometric studies have long struggled to identify carbon leakage, it is perhaps because ambitious policies examples were relatively scarce. Recently, it has been possible to document such leakage. In fact, according to the Commissariat Général au Développement Durable (2020), France’s domestic emissions fell by around 20% over the period 1995-2019, but its carbon footprint increased over the same period by 7% due to a 72% rise in emissions associated with imports. This raises concerns about the effectiveness of European climate policies or, worse, the stalling of European ambitions themselves.

According to the European Court of Auditors (2020) the sectors at risk of carbon leakage (steel, cement, chemicals, paper, etc.) and benefiting from free allowances will account for 94% of industrial emissions during phase 4 of the EU Emissions Trading System (2021-2030). Calibrated on the most efficient installations in terms of emissions for each sector, these free allowances do not cancel out the incentives to decarbonise. However, they have been allocated in too large a number. It is difficult to eliminate the allocation of free allowances for industries that are highly subject to international competition and that suffer from unfair competition from countries with lower or no ambition in this area.

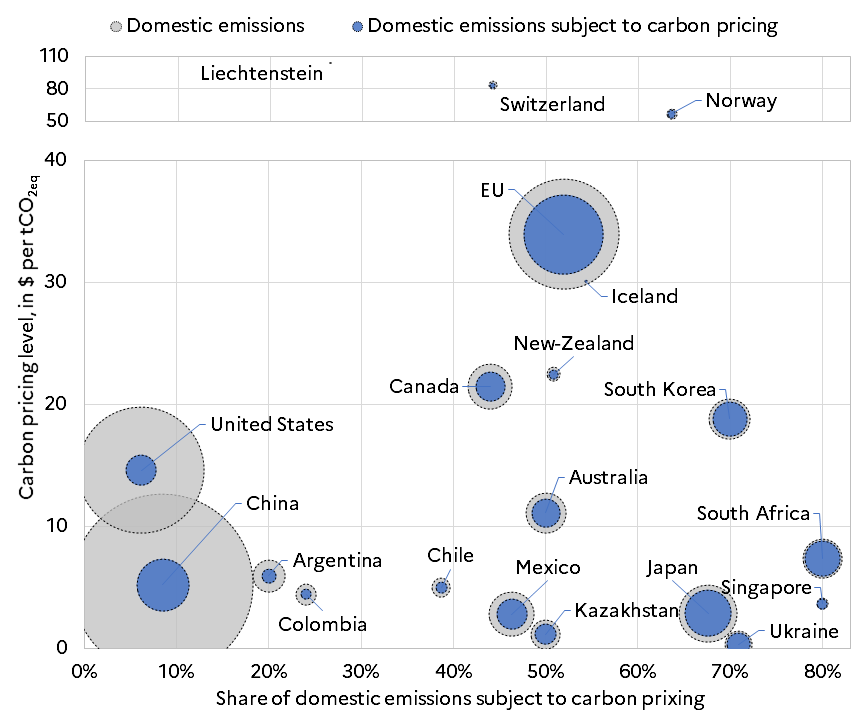

There are also difficulties regarding with public opinion. According to the survey conducted in France by Thomas Douenne and Adrien Fabre (2019), French people are on the whole very much opposed to the idea of using carbon pricing in order to change behavior and thus fight climate change. They are skeptical about the effectiveness of such a mechanism, which they see essentially as a pretext for raising taxes, or even as a license given to the wealthiest households, who will be able to buy their way out of any constraints. The idea of a Pigouvian tax the revenues of which would be redistributed to low-income households or even to the middle class – an idea supported by many economists and in particular by the Conseil d’analyse économique and the Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires – is also rejected by the respondents. They individually seem to underestimate the net gain that such a policy could bring them, even when they receive precise information about it. Only the tax on kerosene seems to get their support, perhaps because most of them believe they are not subject to it, at least not directly. Conversely, they are in favour of norms and regulations, even though their implicit cost is often higher than the one of a tax. They also support public investments, the ultimate financing of which remains unclear and which are generally considered by economists as a complement rather than a substitute for pricing (see Bureau, Henriet and Schubert, 2019). In general, the real and perceived fairness of climate change policies seems to be a sine qua non condition for its success. In this respect, international burden sharing is a key element, as Europe accounts for less than 10% of global emissions. Indeed, carbon pricing in Europe already appears high in international comparison (see figure below), although it will need to increase further if the EU is to meet the Paris Agreement targets.

Graph: Status of carbon pricing in the world in 2020

Note: The levels of carbon pricing and territorial emissions coverage are those of 1st November 2020. For the EU, its ETS and the carbon taxes implemented by its Member States, including France, are taken into account through a weighting. Local and regional initiatives are taken into account for China, Canada, the United States and Japan.

Source: L’Heudé, Chailloux and Jardi (2021), French Treasury based on data from World Bank (2020). Carbon Pricing Dashboard.

Don’t lose sight of the real target

If the introduction of a CBAM is necessary in order to strengthen European policies against global warming (see L’Heudé, Chailloux and Jardi, 2021), those who dream of making foreign companies bear the costs of our policies will be quite disappointed.

To be compatible with the rules of the World Trade Organisation, the CBAM must be non- discriminatory, i.e. it must apply the same treatment to imported goods as to European products. Thus, carbon pricing could be based on that of the EU ETS and take into account the climate policies of third countries and their level of development. It will also be necessary, inevitably, to phase out the free allocation of allowances to European industry.

Furthermore, the CBAM will automatically increase the costs of downstream companies: if imported steel has to pay for carbon allowances, then the European automotive industry, which consumes steel, could suffer from competitiveness loss compared to its non-European competitors on third markets and even on the internal market (as long as this downstream sector is not itself covered by the CBAM). In addition to this effect, European exporting companies will suffer the loss caused by the gradual phase out of free allowances. In a recent study, Cecilia Bellora and Lionel Fontagné (2021) estimate that a CBAM affecting imports of the most carbon-intensive goods (in particular steel, cement, chemicals, aluminum, refining, paper and glass) at the level of the European pricing would reduce European exports by around 1.5%, which raises the question of compensation.

This is why the implementation of a CBAM can only be gradual and accompanied by intense diplomatic action to ensure that as many countries as possible (particularly the United States, which recently returned to the Paris Agreement) implement ambitious climate policies, which will make it possible to adjust as closely as possible the scope of the CBAM and, if necessary, to deal with its undesirable effects.

Ultimately, the implementation of a well-calibrated CBAM should incentivize third-country producers to engage in low-carbon production. The CBAM is neither a means to make others pay, nor is it designed to improve the competitiveness of European companies. Its role is to strengthen the effectiveness of climate policies and to enable better international coordination on the subject. And its success will ultimately mean… its demise.

Read more :

>> Version française : Europe taille 55

>> All posts by Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, chief economist – French Treasury